When I made plans for my first visit to Taiwan, a friend

asked if I needed a visa for that country, then corrected himself. “Is it

actually a country? What do I call it?” Despite having lived in Asia for

several years by this point, I was a bit ashamed that I didn’t know the answer

to that question. Now I realize there was no need for shame – not even the Taiwanese can agree on their status.

When I made plans for my first visit to Taiwan, a friend

asked if I needed a visa for that country, then corrected himself. “Is it

actually a country? What do I call it?” Despite having lived in Asia for

several years by this point, I was a bit ashamed that I didn’t know the answer

to that question. Now I realize there was no need for shame – not even the Taiwanese can agree on their status.

Most of us in the West are at least vaguely aware that

Taiwan is in limbo, terrified that an outright declaration as an independent

country could trigger a war with China, which claims Taiwan as a rogue break-away

state that will one day be reclaimed. But it wasn’t until I lived in both China

and Taiwan that I really understood the history of this complicated

relationship.

The first time I was forced to contemplate the matter in any

mindful way was in Shanghai during my first job as an editorial staff member. The magazine was in

English with a mostly expat audience. We ran an article on meat-eating habits

in China, or something of the sort. What I remember most was the illustration

that ran with the piece – a cow with its body sectioned off into its various

parts. Instead of being labelled shank, sirloin, chuck, etcetera, they were

given names of China’s various provinces.

Every magazine in China is assigned a state “publisher”,

which is just a noble euphemism for “censor”. At the last minute before

publication of the meat item, our censor noticed that the cow didn’t encompass

Taiwan. An amendment was insisted upon.

This incident was regaled for days by the incredulous staff

as an example of the most absurd of China’s efforts to include Taiwan in its

modern narrative. The joke, of course: What part of the cow could possibly

represent islands not attached to the mainland? From what I recall, Taiwan was

nonsensically slapped onto the illustration to please the authorities. In the

end, though, it rather disparagingly looked like a puffy methane cloud

emanating from the cow’s rear.

I had to wonder why this rather trivial matter became a

subject of outrage among our mostly Western staff – “How dare they try to claim Taiwan! In

our pages!” – considering that there were far more egregious instances of

censorship that we gladly swallowed in every issue. I didn’t see the point of

getting riled up over having to play along with China’s claim on the region,

despite my support for Taiwan’s independence. Let China try to claim Taiwan or

Antarctica or Micronesia for all I care. On this file, China has been all talk

and no action – and when you look at what action they DO take on other files

(jailing and torturing political dissidents, for instance), trying to occupy

Taiwan by means of a cartoon cow should have been the least of anyone’s

concerns. In fact, such deeds only underscore China’s impotence with regards to

Taiwan. While the government in Taipei issues passports, prints its own money,

delivers health care and other programs to its citizens, all Beijing can do is

draw the island on its maps. China’s failure to govern Taiwan would be less

obvious if they didn’t make such a big deal of it, especially when it comes to

cartoon animals in English-language magazines. But I digress.

By the outrage that spread through the office, I realized

what a strong knee-jerk reaction Westerners are conditioned to when it comes to

Taiwan. For those of us foreigners living in China, we gladly didn’t mention

“June 4” in public, because I suppose the fallout from the Tiananmen Square

sock-hop was an internal housekeeping issue that didn’t affect us directly. But

Taiwan – Democracy! Capitalism! – is just too close to our hearts. Growing up

during the Cold War in the 1970s, we were habituated to recognizing any country

that stood up to Communism as a nation of heroes, even if they were being

governed by their own autocratic dictators.

It’s one thing to learn about an issue in classrooms or

documentaries, or to understand an argument by reading different viewpoints.

But I didn’t have any visceral sense of the situation until I lived in Taiwan

for a few months and spoke with friends and their families about how the split

from China has affected their lives and relationships with each other.

The Taiwanese are fiercely

political and will deluge you with their views if you express even the most

remote interest. While those in China will simply echo the standard “Taiwan is

ours” rhetoric, the Taiwanese positions are more compelling because they face

more complex issues about whether to claim independence, re-join China, or live

with the status quo. Let’s put it this way: the Taiwanese are just as biased as

the Chinese, but the Taiwanese biases are far more colourful.

Here’s the history in a nutshell: China enters a modern age

of sorts in 1912, with the end of dynastic rule. After thousands of years of

being governed by emperors, Sun Yat Sen and later Chiang Kai Shek become the

country’s first modern presidents. In 1949, When Mao Zedong and the Communists

take power in a revolt, Chiang Kai Shek, his military, their families, and

thousands of followers flee to Taiwan, where they set up shop as the exiled

government of China. The idea is that this displaced government – called the

Kuomintang (pronounced Gwo-min-dahng) – will one day rule China again

when the Communists are defeated. Both sides – the Kuomintang and the

Communists – consider Taiwan territory of China. The only thing they disagree

on is who the legitimate government of China is.

But now several generations have passed, and the vast

majority of Taiwan’s inhabitants have only known life under their own

democratically elected governments. Meanwhile, the Communists only strengthened

their grip in China and show no sign of budging.

|

| Flag proposed by Taiwan's independence movement |

Time has blurred some of the lines between these divisions.

It was easier to take a clear-cut position back when China was isolated behind the Red Curtain and cut off from modern economies. In those days, Taiwan and Japan were the economic giants of Asia. But

China is now open and fiercely capitalist, and they've been able to choke off a large portion of Taiwan's economy. As a result, a massive sector of Taiwan’s

jobs and factories are flowing towards the mainland. Given China’s population

of 1.3 billion to Taiwan’s 23 million, this has made Taiwan a deferential

partner in cozy trading relationships with China.

As a result, Taiwanese are more likely to consider the

practicality of their vote. Although a majority of Taiwanese today are

pro-independence, enough of them are so concerned about jobs and the economy

that they will vote for pro-China leaders. “No reason to poke the tiger,” one

friend told me. On the other hand, for those who come from pro-unification

families, enough time has passed that many of them don’t feel as strongly as

their parents do about the issue, and tend to think that independence wouldn’t

be such a bad idea.

Regardless, divisions still exist, and you still find families

whose political leanings run through their blood. One of my closest friends

told stories about his family’s land being stolen by Chiang Kai Shek’s men 60

years ago. Yet another friend, this one from a pro-China family, talked about

being ostracized in the schoolyard by other children who said he was not a

“real Taiwanese.” He told me: “My family came here 100 years ago. Their

families came here 400 years ago. So what? We all came from the same place.”

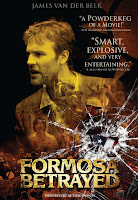

In Taipei, with my ardently pro-independence friend and his

father, we watched a movie called Formosa Betrayed (Formosa being the name of

Taiwan pre-revolution). It tells the tale of a Taiwanese academic assassinated

on American soil to prevent him from completing a book he was writing about Kuomintang

atrocities. It’s 1980, and a CIA agent takes his investigation to Taiwan, where

he gets drawn into more intrigue and gets a few history lessons literally

beaten into him.

In Taipei, with my ardently pro-independence friend and his

father, we watched a movie called Formosa Betrayed (Formosa being the name of

Taiwan pre-revolution). It tells the tale of a Taiwanese academic assassinated

on American soil to prevent him from completing a book he was writing about Kuomintang

atrocities. It’s 1980, and a CIA agent takes his investigation to Taiwan, where

he gets drawn into more intrigue and gets a few history lessons literally

beaten into him.

My friend and his father paused the movie at various points

to add their own anecdotes to the movie’s narrative. “Yes, this is exactly what

happened to us under Chiang Kai Shek!” was the gist of their message. The film

ends with a closing scrawl: “Because of the events depicted in this film,

Taiwan is now a democracy.” My friend teared up a bit and said, “Please show

this movie to your friends in Canada so they understand Taiwan.” When I watched

the movie later with a Taiwanese friend from a pro-China family, his reaction to the

closing scrawl was, “What bullshit!”

What I found delightfully captivating about these types of

conversations was that I had never heard my Taiwanese friends in Vancouver

speak so passionately and politically. I suppose there was no reason for them

to talk shop about their mother country among Canadians like myself. Even when

it came to the whole Taiwan/China dispute, it was something that my Chinese and

Taiwanese friends seemed indifferent about, at least on the outside. But in

Taiwan, it was revealing and somewhat enthralling to witness the political

fervour that bubbles on the surface of their daily lives.

There were times when I felt compelled to take a side.

Really, though, it was not any of my business as a foreigner, but this is who I

am – I like to know a country by planting some roots and embracing as many

aspects of local living as possible. That includes understanding the nation’s

issues and politics. As the famous phrase goes, “the “personal is political”,

and the Taiwanese are a magnificent example of this adage. Understanding a

nation’s politics well enough to form an opinion was my way of feeling a sense of belonging and engaging with

the country around me, so wherever I lived I'd pick up the paper and start talking about what I read. (Some friends I made in

these places admired this penchant; others found it annoying.)

Nowadays, whenever I read an article in the Canadian press

about Taiwan, I don’t react with, “Well, that was interesting.” I’m either

agreeing or calling “Bullshit!”

The latter category is how I reacted to this article in a

Vancouver weekly newspaper. In it, several Taiwanese immigrants to Canada

complain about the gutlessness of powerful nations to stand up to China and

officially support Taiwan independence. Reading their statements, I was

reminded of something one friend in Taipei told me. When I talked about how my

Taiwanese friends in Vancouver seemed so different from the Taiwanese in

Taiwan, his explanation was that those who leave to hold foreign passports are

more inclined to lay low in a safe haven until the dust settles in their

homeland. This means being apolitical and a little bit "disloyal to the cause," or so I was told.

So when I read these types of comments from Taiwanese Canadians, such as that

Taiwan is “virtually an orphan, and this goes on because all the strong nations

tolerate that,” I can’t help but think that it’s not just strong nations that

are to blame – you could also say that those who abandoned the cause and fled

Taiwan are just as culpable.

Many Taiwanese, such as those quoted in the

aforementioned article, want the powerful countries of the world to cut ties

with China in support of Taiwan. They want our governments to officially open

embassies in Taipei, and our businesses to stop trading with the world’s

second-largest economy in favour of the nineteenth largest. This is

hypocritical, though, since Taiwan itself has formed many rewarding trade

agreements with China, and they've done so with the backing of the people – the ruling Kuomintang party has won two elections in

a row on a pro-China platform. Even the pro-independence party, the Democratic

Progressive Party, softened its stance toward China to win two elections in 2000 and 2004. Why wouldn’t the DPP declare independence, despite that being

their raison d'être? As one friend put it, nobody wanted them to “poke the

tiger”.

This is where both sides of the Taiwan/China argument ring

hollow. I don’t fault the Taiwanese for being cautious with regard to China.

But they must also live with the fact that their approach leaves them open to

being claimed by a more powerful country, and currently that’s China. If the

Taiwanese want other nations to poke the tiger, they must poke the tiger first

and make a clear declaration for the rest of the world to rally behind. I’m not

suggesting that it’s easy – China’s official position is to attack Taiwan if it

tries to secede (I don’t think it would come to that, but who really wants to

find out the hard way?). It’s ludicrous, however, to ask other nations to

antagonize China while Taiwan continues to profit from their own cozy

relationship with the tiger.

Beijing itself is just as full of hot air. If Taiwan belongs

to them, then why don’t they send their bureaucrats there to collect taxes,

issue passports, supervise the military, print money, and plant their flag on

every government building? A country is defined by its ability to control its

borders, service its armed forces, and provide for its people. Beijing is

unable to do any of these things in Taiwan. So how can they claim it as their

territory?

I think it’s inevitable that Taiwan will be forced to

re-join China at some point in the near future. Not through hostile means, but

economic ones. The more reliant Taiwan becomes on China and its market, the

more influence and power China will have in Taiwan’s affairs. Taiwan is already

in China’s tentacles, and the merger will be a slow and gradual one. (But I’m

also naively optimistic that China will transform over time and adopt some

characteristics of a democracy, which would only encourage the reunification.)

For those reasons, I’m uncertain how I’d feel if I were a

Taiwanese citizen with a real stake in the game, not just an opinionated

foreigner. I would certainly be pro-independence, but I wonder how hard and how

loudly I’d fight for it. As much as I’d fear getting too close to China, I’d

have the same basic concern about my job and living standard, not to mention a

potential war. Although I like to think the personal is political, the modern corollary to that saying should be, “... and the political is monetary”. As governments the world over are taking on more

characteristics of being business managers while letting the free market chip

away at our social programs, the day may soon come when it doesn’t matter which

country we’re a part of. As for China, they're taking a very business-like approach to Taiwan: instead of attacking, they're simply buying them out.

For a better grasp on Taiwan's political realities, this article by Canadian historian Gwynne Dyer, posted just after Taiwan's 2012 presidential elections, gives a succinct and modern perspective on the thinking behind their current relationship with China.

For a better grasp on Taiwan's political realities, this article by Canadian historian Gwynne Dyer, posted just after Taiwan's 2012 presidential elections, gives a succinct and modern perspective on the thinking behind their current relationship with China.

.jpg)