As the owner of more than one hard-to-find Beatles record, I know a good deal (or a bad one) when I come across it. But rarely do I come across a deal that's blatantly suspicious. For instance, the other day, when I found myself staring at one of the rarest LPs in the world – one I have seen stickered at $4,000 and had to travel all the way to Tokyo to see – for $34.99. Yes, the decimal was in the right place.

There it was as I strolled into Beat Street Records on

Hastings Street, the legendary "butcher cover" staring at me from the

front of the Beatles rack. I knew something was fishy even before I saw the

price tag. First of all, anyone who owns one of these doesn't stick them for

sale in a record bin. You hold onto it at home and advertise for the highest

bidder. And if you're the owner of a record shop looking to show it off to customers,

you keep it locked in a glass case behind the counter. And if your shop is on

Crack Row (Hastings Street), around the corner from Blood Alley (real name),

you don't keep it in the shop at all.

So it was no surprise when I saw the "cheap" price

tag, because I had already surmised that this was a reproduction. The only question

left: was it an official repro or a fake?

This was the first time I had encountered any form of the

butcher cover in Canada. In Japan I saw three. Strangelove Records in the Shinjuku district had a

butcher cover behind the counter. It wasn't for sale, but the clerk took it

down and let me hold it. That alone was a thrill. Vinyl Records nearby had a prime

specimen on the wall, going for C$4,000 (the shopkeeper wouldn't let me photograph it). The

RecoFan outlet in Shibuya had one with a big rip through John Lennon's face (pictured), a

sign that this was a "bad peel job", as they call it in butcher-collector

circles. Some of the butcher covers had been "corrected" by Capitol

records by pasting the new cover over the old one. Those who bought a

paste-over inevitably would try to steam or peel it off, usually ruining the

product altogether, but not to the point of making it worthless – this

"peel job" in Shibuya was being offered for C$2,500.

This was the first time I had encountered any form of the

butcher cover in Canada. In Japan I saw three. Strangelove Records in the Shinjuku district had a

butcher cover behind the counter. It wasn't for sale, but the clerk took it

down and let me hold it. That alone was a thrill. Vinyl Records nearby had a prime

specimen on the wall, going for C$4,000 (the shopkeeper wouldn't let me photograph it). The

RecoFan outlet in Shibuya had one with a big rip through John Lennon's face (pictured), a

sign that this was a "bad peel job", as they call it in butcher-collector

circles. Some of the butcher covers had been "corrected" by Capitol

records by pasting the new cover over the old one. Those who bought a

paste-over inevitably would try to steam or peel it off, usually ruining the

product altogether, but not to the point of making it worthless – this

"peel job" in Shibuya was being offered for C$2,500. |

| Capitol's recall letter; click to enlarge |

I should back up and tell you what makes this cover such a

prize. To begin with, this wasn't even a formal Beatles record. The group had always taken great care in sequencing the songs on their British LPs, giving

good value for money with 13 or 14 tracks. However, the American label that had

rights to the songs on this continent – Capitol Records – would issue the LPs a

few tracks short, then collect the missing songs onto compilation records, of

which this was one. When Yesterday and Today was ready to hit the

American marketplace in June 1966, Capitol called up the group's management to

request a cover. This is what they got. The fact that Capitol even used

the image was out of character, as the American label had a habit of tarting up

and dumbing down the arty British covers by adding garish colours and

simple-minded photos to make them more consumer-friendly. Capitol realized

their "mistake" on this one and recalled the album after only a day

on the marketplace. The fact that some retailers refused to stock the record

helped them with the decision. Those who actually bought this one-day-only

record landed themselves a rarity.

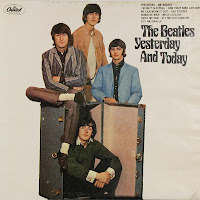

The album was re-released the following week with a new, innocuous cover, one showing the boys huddled around a steamer trunk.

The album was re-released the following week with a new, innocuous cover, one showing the boys huddled around a steamer trunk.

Many fans theorized that the submission of the original cover was the

Beatles' way of protesting Capitol's "butchering" of their records.

That would have made a great story had it been true, but sadly this wasn't the

case.

At Beat Street Records, I approached the gangly, middle-aged

clerk at the cash desk. I don't want to knock the guy personally, but, although

he fit right in with a Hastings five-and-dime, this wasn't the font-of-all-knowledge

used-record-store-clerk I was familiar with. I'm used to bantering with

record-shop clerks who regale me with stories about whatever piece of

vinyl I approach them with. Sometimes these guys are entertaining and

informative. Sometimes they're pricks. (See the film High Fidelity for

some hilariously piercing portrayals.) Either way, these guys know their stuff.

Except at Beat Street.

"Uh, yeah. That's part of the catalogue re-mastering

they just did."

No, the recent catalogue re-issues comprised all the

British LPs, not the American ones, and certainly not with this

out-of-commission cover. So I explained the history of this particular record.

"Yeah, I can see that," he said, starting to

grimace. "I never really looked at it, but yeah, it's kinda weird, right?

Like, what does all that have to do with the title? Like, Yesterday and Today and slabs of meat? That's just demented, man."

I took the LP out of the sleeve for examination. Not only

was it in beautiful condition, without any evidence of being pre-owned, it was

on 180-gram, marble-blue vinyl – the kind of refined touches marketed specifically

to collectors. So, for the moment, a seed was planted that this might be an official

re-issue of some kind. Bootleggers would never go to such lengths, would they?

Despite how much I loved the record, though, I was apprehensive. I put it back in its place and left to do some online research. No official pressing for sale on Amazon. Nothing on the Beatles collectors' websites. Googling "butcher cover re-issue" and such came up with evidence of a limited re-pressing in Japan (on red or sky-blue vinyl, not the marbled light blue I saw), but this was just unofficial chatter on message boards, and others were replying that the Japan pressings were unofficial. Regardless, I figured I'd go back to Beat Street and pick it up. The mystery made it more appealing.

Despite how much I loved the record, though, I was apprehensive. I put it back in its place and left to do some online research. No official pressing for sale on Amazon. Nothing on the Beatles collectors' websites. Googling "butcher cover re-issue" and such came up with evidence of a limited re-pressing in Japan (on red or sky-blue vinyl, not the marbled light blue I saw), but this was just unofficial chatter on message boards, and others were replying that the Japan pressings were unofficial. Regardless, I figured I'd go back to Beat Street and pick it up. The mystery made it more appealing.

A

different clerk this time, someone more High Fidelity and less

straight-outta-rehab, but still not all that up to speed on his stock.

"What's the deal with this record?" I asked.

"Who re-issued it?"

"I dunno," he shrugged. "It was in the last

shipment from the distributor."

"Yeah, but is it an import? Did it come from Japan, or

what?"

"I dunno. It was in the box the distributor sent."

I was taking the evasiveness as a sign that I was likely

about to purchase a fake. But it's a beautiful fake. Despite the flawless sound, there is one giveaway upon playing the record that this is not a genuine article. The sound mix is in mono, as the label states. However, the manufacturers of this piece used the stereo mixes and folded them down into mono, rather than using the original mono tracks. (The backwards guitar on "I'm Only Sleeping" differs between the mono and stereo version, a noticeable tell for collectors.) An unfortunate oversight, as the mono tracks have been readily available on CD since 2009.

I'll chalk it up to kismet that I discovered this just a few blocks from Vancouver's east-side institution, Save-on-Meats – an ideal locale to find a butcher cover for only $34.99.

I'll chalk it up to kismet that I discovered this just a few blocks from Vancouver's east-side institution, Save-on-Meats – an ideal locale to find a butcher cover for only $34.99.

~~~~~~~

Here's what to those who knew best had to

say about the most infamous album cover in pop-music history (quotes from Anthology, published in 2000, with a wee bit

of paraphrasing):

George: An Australian photographer called Robert

Whitaker came up to London. He was avant garde. He set up a photo session which

I never liked at the time. I thought it was gross and stupid. Sometimes we did

stupid things, thinking it was cool or hip when it was naïve and dumb, and that

was one of them. It was a case of being put in a situation where one is obliged

as part of a group to co-operate. Quite rightly, somebody took a look and said,

"Do you think you really need this as an album cover?"

John: By then we were really beginning to hate photo

sessions. It was a big ordeal and you had to look normal and you didn't feel

it. Robert Whittaker was a bit of a surrealist and he brought along all these

dolls and pieces of meat, so we really got into it. I don't like being locked

into one game all the time, and we were supposed to be sort of angels. I wanted

to show that we were aware of life, and I really was pushing for that album

cover, just to break the image. It got out in America. They printed about

60,000, and then there was some kind of fuss, and they were all sent back or

withdrawn. Then they stuck on that awful-looking picture of us looking

deadbeat.

Paul: We'd done a few sessions with Robert Whittaker

before and he knew our personalities. He knew we liked black humour and sick

jokes. I don't know really what he was trying to say, but it seemed a little

more original than the things the rest of the photographers were getting us to

do.

Ringo: I don't know how we ended up sitting in

butchers' coats with meat all over us. The sleeve was great for us because we

were quite a nice bunch of boys and we thought, "Let's do something like

this." What was crazy about that sleeve was that, because it was banned,

they glued the new sleeve over it and everyone started steaming it off. They

made it into a really heavy collector's item.