I'd always had a hard time letting go of the CBC. Like a first relationship, I always remembered this job as my first and fondest. Bouncing around various departments on temp contracts for eight years was a wondrous experience. You see, the CBC was a vital part of Canada's identity for its first 60 years or so, and growing up in this country meant being influenced by the broadcaster in some shape or form. Even when the CBC wasn't being Canadian, it was not Canadian in a very Canadian way. The fact that we could watch British sitcoms and arty US films on a major network, for instance, set us apart from the Americans. And when we watched Sesame Street, we knew if we had tuned into an American channel or CBC based on the second-language skits – Americans had Spanish-speaking puppets, we had Kermit le Frogge.

During my broadcasting course at BCIT, I started to feel

more disinterested and unresponsive to commercial radio, and my dial drifted

toward CBC Radio more frequently. CBC Radio, unlike the TV side, was one of

those things I had neglected pretty much my entire life. It was such a

revelation just to hear interesting people talk every day without obnoxious

commercials and loudmouthed sportscasters. When I mentioned to my BCIT

instructors about my choice of station on my drives to and from school, I was

told, “Get your mind off CBC right now. You'll never work there. They're

unionized, and they do things very differently from the stations you're going

to work at.”

During my broadcasting course at BCIT, I started to feel

more disinterested and unresponsive to commercial radio, and my dial drifted

toward CBC Radio more frequently. CBC Radio, unlike the TV side, was one of

those things I had neglected pretty much my entire life. It was such a

revelation just to hear interesting people talk every day without obnoxious

commercials and loudmouthed sportscasters. When I mentioned to my BCIT

instructors about my choice of station on my drives to and from school, I was

told, “Get your mind off CBC right now. You'll never work there. They're

unionized, and they do things very differently from the stations you're going

to work at.”

Upon graduation, I submitted only one job application – to

CBC Radio. As luck would have it, they had a temp opening in their "tape

supply" room. Now, where else would anyone get a job splicing used, heavily

edited recording tape into fresh product? Or spooling new, un-encased tape into

empty reels? Or fast-forwarding miles of used tape through a reel-to-reel to

check for quality? Twice a day, I'd make my rounds, through the newsroom, the

current-affairs studios, producers' offices and edit suites to collect used

tape. It was a surreal job, and I got to take my breaks hanging out with David

Wisdom as he produced his uber-cool after-midnight show Nightlines, or in the

back of the Studio 5 control room on my lunch hours watching Fanny Keefer host

Almanac.

When that temp contract ran out, I was shuffled into other

jobs as vacancies demanded – program assistant for Vicki Gabereau for a year,

music programmer for a few shows, and even picking up freelance production work

on weekends. But the one area of CBC Vancouver where I was assigned the most

was the record library.

When that temp contract ran out, I was shuffled into other

jobs as vacancies demanded – program assistant for Vicki Gabereau for a year,

music programmer for a few shows, and even picking up freelance production work

on weekends. But the one area of CBC Vancouver where I was assigned the most

was the record library.

While the work in the library could be tedious and wearisome

(lots of data entry and re-shelving), it was also one of the most stimulating

parts of the building. The library was a salon of sorts. Production staff from

a wide variety of shows, from current affairs to pop to classical to news,

would randomly flit in and out of the library, roping us into a wide gamut of

conversations. There'd be the Afternoon Show producer who'd come down and say, "We're interviewing a UFOlogist, so, can you think of any good songs about

flying saucers?" Or the news guy who practically busts the door down in a

panic: "Jim Henson just died. Where are the muppet records!?" And the languid

Gabereau music guy who never needed any help, because the show was pre-taped

and no one was in a panic there.

The library was the heart of CBC Radio. It was our community

centre, our church, our confessional. It wasn't where the shows were made, it

wasn't where the action happened, but it was the only place in the building

that brought everyone together, and always in random, serendipitous ways. When

someone had something to get off their chest, whether office politics, world

affairs, union politics or just a bit of gossip, it was we librarians (and

whoever else was in earshot) who became their sounding boards.

And there was music around. Always. Whether it was a

producer skimming tracks in a listening booth, or head librarian Judy sampling

the programming in her office, or soon-to-be-head librarian Johnny pulling out

an old easy-listening record at the end of the day, this library was not a shhhhhh zone.

Fast forward through 15 years. I'm laid off due to deep

government cuts. I land work with Health Canada and become the accidental

medical case manager (work I never imagined doing, let alone being good at, but

it broadened my mind while paying the bills). Ten years after that, an itch to

get back into media and do some travelling found me working as a magazine

editor in China and Singapore, with a brief stint studying in Taipei.

You'd think that with all that life experience, now being in

my 40s, I would have put the CBC of my 20s well into my past. But there was

something about the place that always called me back. During my work for the

feds, I freelanced on-air for the occasional pop-music show. When the feds went

on strike a couple of times, I found some work back in the library covering for

holidays. When I came back for the Olympics between jobs in Singapore, I got a

couple of days of grunt work for some of the live special programming. I could

have thought, “Magazine editor, overseas resident … why am I running to Staples

to buy Jian Ghomeshi coloured file folders?” Because I never, ever got over

that CBC feeling from when I was 21. The CBC still felt, as it always had, like a very egalitarian place, where people (for the most part) worked collectively on projects they were proud of, and less like a hierarchy of individuals.

When I returned from Singapore for good in 2011, word got

out that I was looking for work, and Johnny (now the lone librarian after

several years of cuts chipped away at the large staff) called me up with an

assignment. The good news – he needed someone in the record library for a few

weeks. The bad news – the job entailed dismantling the collection of records

and CDs, and archiving the valuables before auctioning the rest of it off.

These few weeks were full of emotions surreal, beautiful,

sad, and poignant. From the time I left the CBC at age 29 to being called back

at age 45, I was certainly a changed person. Not just more mature and with

enhanced skills, but having been both scarred and bettered by new careers and

exposure to different parts of the world. This part of my past should have been

well behind me. Coming back to work amongst the stacks of records and compact

discs, doing the work of my youth – it should have felt like one grand backward

step. Instead, it felt otherworldly. This institution was deeply embedded into

my identity, seamlessly flowing through childhood, my student years, and my

working life. Of course it was devastating to see the library taken to pieces,

just as most of the CBC building on Hamilton Street had been transformed

through the years. Yet, no matter how much of a mistake I believed it was to

dispose of the library, I'm glad I was back for its final days.

These few weeks were full of emotions surreal, beautiful,

sad, and poignant. From the time I left the CBC at age 29 to being called back

at age 45, I was certainly a changed person. Not just more mature and with

enhanced skills, but having been both scarred and bettered by new careers and

exposure to different parts of the world. This part of my past should have been

well behind me. Coming back to work amongst the stacks of records and compact

discs, doing the work of my youth – it should have felt like one grand backward

step. Instead, it felt otherworldly. This institution was deeply embedded into

my identity, seamlessly flowing through childhood, my student years, and my

working life. Of course it was devastating to see the library taken to pieces,

just as most of the CBC building on Hamilton Street had been transformed

through the years. Yet, no matter how much of a mistake I believed it was to

dispose of the library, I'm glad I was back for its final days.

How much this place, this room, had haunted me. Stepping

back into it, after all I had been through in my life, was almost illusory. There

was my handwriting still on the signs and shelf-tagging. The desk, a bulky

thing probably handmade by the TV stagecraft department, still had all the same

scratches and pen marks indelibly etched into it. The chairs hadn't been

replaced. The clutter in the drawers and cubby-holes hadn't changed. The same

tattered recycling box was still under the desk. Funny how things like scrapes

or dents or recycling boxes are not meant to make any impression whatsoever,

but the memories that come back when you see them again after 20 years! Even

the phone still had my voice on the outgoing message, back from the day in the

early 90s when voicemail came to the building.

A couple of my friends in Singapore responded to my Facebook

posts that I was demeaning myself by doing menial labour, or "janitor" work, as

one of them put it. Of course, they knew me as the well-off magazine editor.

Now they were seeing me sitting on the floor, sorting through stacks of musty

records. But their comments only underlined the reasons why I left that

country. The Singapore work culture is ruled by kiasu, a local term that

roughly means "fear of losing face". Meaning, if you're a professional, you're

not caught dead doing minor tasks or manual labour best left for a secretary or

cleaner. For instance, going for lunch with sales staff at one magazine I

worked for, we could not find an empty table at the food court, except for one

cluttered with dirty dishes. To their horror, I picked up the dishes and wiped

the table with a napkin. "Don't do that!" one of them said. "Let's find another

spot," said another. Although we ended up with a clean table without waiting,

one colleague said I had made a spectacle by doing "the uncle's

work". That's just one of many illustrative stories of kiasu that I came

home with.

A couple of my friends in Singapore responded to my Facebook

posts that I was demeaning myself by doing menial labour, or "janitor" work, as

one of them put it. Of course, they knew me as the well-off magazine editor.

Now they were seeing me sitting on the floor, sorting through stacks of musty

records. But their comments only underlined the reasons why I left that

country. The Singapore work culture is ruled by kiasu, a local term that

roughly means "fear of losing face". Meaning, if you're a professional, you're

not caught dead doing minor tasks or manual labour best left for a secretary or

cleaner. For instance, going for lunch with sales staff at one magazine I

worked for, we could not find an empty table at the food court, except for one

cluttered with dirty dishes. To their horror, I picked up the dishes and wiped

the table with a napkin. "Don't do that!" one of them said. "Let's find another

spot," said another. Although we ended up with a clean table without waiting,

one colleague said I had made a spectacle by doing "the uncle's

work". That's just one of many illustrative stories of kiasu that I came

home with.

I was not the only former employee to be brought back for

the library project. Two retired producers were also brought on board for their

expertise, both of them well-regarded not just at the CBC, but in the local

arts community. So here we all were: a former librarian, one of the city's top

recording engineers, and a respected jazz producer, all using our respective

expertise in pop, classical and jazz to select prime specimens for archiving,

mucking about in stacks of records and having a blast. This is how my work

abroad enhanced my appreciation for life in Vancouver – I was now back in a

place where I didn't have to fear for my social status based on the job I did

or how I appeared to others. Sitting on the floor of the library, rummaging

through old records, not only was I happy to be back "home" in the CBC, but I

was also relieved to be amongst familiar colleagues who could be both

professional and laidback.

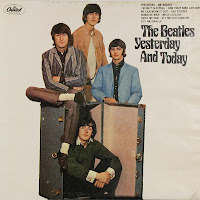

Our jobs required us to look at every single record on the shelves,

a collection going back to the early 1960s. You can imagine, all of us music

lovers, finding massive distractions amongst our work. I ended up volunteering

a few hours or days here and there to make up for the time spent listening to

weird discoveries in one of the listening booths.

Our jobs required us to look at every single record on the shelves,

a collection going back to the early 1960s. You can imagine, all of us music

lovers, finding massive distractions amongst our work. I ended up volunteering

a few hours or days here and there to make up for the time spent listening to

weird discoveries in one of the listening booths.

All of us who worked on this sad project lamented the

mistake of disposing of such a massive library, yet our attitude was: "If it's a done deal, then glad we're the ones doing it." On the one hand, I could see

the corporation's reasons. With so much of the library's contents digitized and

accessible to studios across the country on their Virtual Music Library, the

physical libraries were becoming largely redundant. On the other hand, it was

only the compact discs, dating back to about 1990 or so, that had been ripped

into the VML. It wouldn't have cost the corp much to have a librarian spend a

year digitizing some of the rare vinyl. Instead it was boxed up and shipped to

CBC Toronto, where, we surmised, the collection might likely sit untouched for

several years.

The value of this "redundant" library was underscored while

I was boxing up a stash of local discs by Vancouver bands. There was some

labour trouble brewing in our transit service, and a producer came down looking

for a particular song he remembered about a bus strike in the 1980s. A few North

Vancouver kids had released a single called "Stranded in the Park", sung to the

tune of Bruce Springsteen's "Dancing in the Dark". (Flip side: "Born in North

Van".) I just happened to have that single by Boss and the Bandits in pile in a

listening booth, after having given it a spin myself. The occasion

prompted one technician to grab some of the collection and digitize it himself

before our local treasures ended up in an inaccessible box a few thousand miles

away.

The value of this "redundant" library was underscored while

I was boxing up a stash of local discs by Vancouver bands. There was some

labour trouble brewing in our transit service, and a producer came down looking

for a particular song he remembered about a bus strike in the 1980s. A few North

Vancouver kids had released a single called "Stranded in the Park", sung to the

tune of Bruce Springsteen's "Dancing in the Dark". (Flip side: "Born in North

Van".) I just happened to have that single by Boss and the Bandits in pile in a

listening booth, after having given it a spin myself. The occasion

prompted one technician to grab some of the collection and digitize it himself

before our local treasures ended up in an inaccessible box a few thousand miles

away. The items we selected to save barely scratched the surface

of the entire library. When we finished our project, the reason for the corp's

haste became apparent – after the collection was auctioned off to the highest bidder, the library was converted to retail space. When the CBC Vancouver “bunker”

was built in 1971, it was on the far outskirts of downtown, where there was no

demand for real estate. Today, it's on the edge of trendy Yaletown, and every

part of the building that can be sold off or rented out has been converted and

parceled out. The parking lot is now a condo called TV Towers. The library was

just the latest casualty. One day soon, I suspect, as programming continues to

get cut and become centralized in Toronto, the entire building will be gone.

The items we selected to save barely scratched the surface

of the entire library. When we finished our project, the reason for the corp's

haste became apparent – after the collection was auctioned off to the highest bidder, the library was converted to retail space. When the CBC Vancouver “bunker”

was built in 1971, it was on the far outskirts of downtown, where there was no

demand for real estate. Today, it's on the edge of trendy Yaletown, and every

part of the building that can be sold off or rented out has been converted and

parceled out. The parking lot is now a condo called TV Towers. The library was

just the latest casualty. One day soon, I suspect, as programming continues to

get cut and become centralized in Toronto, the entire building will be gone. But where the parking lot was not missed – nor the plaza

that became a sandwich shop, nor the cafeteria replaced by private offices – the

library was the unofficial heart of the radio operation. Now that it's gone, I

can finally put the CBC behind me. While I would go back if I had a chance, I

no longer feel any calling or attachment to the place.

But where the parking lot was not missed – nor the plaza

that became a sandwich shop, nor the cafeteria replaced by private offices – the

library was the unofficial heart of the radio operation. Now that it's gone, I

can finally put the CBC behind me. While I would go back if I had a chance, I

no longer feel any calling or attachment to the place.

After all the

transformations made to the building and the culture of CBC Vancouver, the loss

of the record library is the last straw that renders the place unrecognizable to me.

.jpg)