Recently there was a strike of unionized bus drivers in

Singapore. In any other city, a strike by civic workers would have no other

significance beyond labour negotiations and public inconvenience. In Singapore,

however, a recent string of otherwise benign incidents (subway malfunctions, a

traffic accident, now the bus strike) has underscored how race and class are

tied in the city-state.

Recently there was a strike of unionized bus drivers in

Singapore. In any other city, a strike by civic workers would have no other

significance beyond labour negotiations and public inconvenience. In Singapore,

however, a recent string of otherwise benign incidents (subway malfunctions, a

traffic accident, now the bus strike) has underscored how race and class are

tied in the city-state.

My first impression of Singapore, based on my first few

travels there between 2003 and 2006, was that the city was culturally diverse and

racially harmonious. In that respect, it reminded me of my home city, Vancouver, and that parallel was one of

the main lures for me to eventually live there. But something gradually started

to feel amiss. Among all the people I met – mainly ethnic-Chinese Singaporeans

– it seemed that all of them had prestigious careers. It was only natural that

I'd meet my fair share of bankers and IBM and Microsoft executives. After all,

Singapore is a major banking and tech hub. But those who didn't have

traditional careers in commerce or computing were in one kind of creative field

or another. Never had I met so many singers (opera, jazz, pop), authors,

composers, architects, graphic designers, publishers, historians and scholars.

I came from a culture where mothers would tell their daughters, "Not every

little girl can grow up to be a ballerina." In Singapore, the sad alternative

little girls have to settle for is being the ballerina's publicist.

I made this observation to a friend, and I asked, “Who picks

up your garbage and bags your groceries?” He said, with a straight face,

“Malaysians.”

Although Singapore had gone to

great lengths to accommodate the mosaic that makes up the nation (mainly

Chinese, Malay, Indian and Filipino), there remained obvious class divides

whose borders were defined by race. About one quarter of Singapore’s population

is made up of foreigners who perform the blue-collar work and manual labour

that Singaporeans themselves don’t. While the far lower wages foreigners demand

is part of the reason, a recent survey of employers also revealed they’re

preferable because they “are flexible in taking up jobs locals avoid.”

Then there are the white Westerners, who are almost without

exception paid above the average wage of the locals, excessively so in most

cases.

When I moved to Singapore in late 2007, some of Singapore’s

façade of racial harmony was starting to crack. It was first noticeable when

rents and property values skyrocketed. A friend of mine with a two-bedroom

apartment had to move in early 2008 when his lease was up because the rent was

about to jump from $2,500 a month to $4,000. Stories like that were suddenly

commonplace. Why? Because of all the rich Westerners flooding into Singapore

who were willing to drop a sack of money on anyone who’d give them what they wanted.

So the backlash against the whites began.

When I moved to Singapore in late 2007, some of Singapore’s

façade of racial harmony was starting to crack. It was first noticeable when

rents and property values skyrocketed. A friend of mine with a two-bedroom

apartment had to move in early 2008 when his lease was up because the rent was

about to jump from $2,500 a month to $4,000. Stories like that were suddenly

commonplace. Why? Because of all the rich Westerners flooding into Singapore

who were willing to drop a sack of money on anyone who’d give them what they wanted.

So the backlash against the whites began.

Next up it was the workers from China. They were in demand

for their willingness to work hard for very low wages. Around the time I

arrived, I was reading letters to the editor from angry locals going on about

not getting restaurant service in English. The complaints were contagious and

I’d hear mutterings once in a while about the “China people” changing

Singapore’s landscape. My own ethnic-Chinese landlord came home one day in a

fury because the 7-11 clerk spoke to him in Mandarin. “Well, you speak

Mandarin,” I said. What’s the problem? “Singapore’s national language is

English! These China workers are eroding our way of life,” and on he went. It

wasn’t the last time I’d hear such complaints.

The peculiar icing on the cake, however, was that the

complaint a few years earlier was the opposite: that Singapore was becoming too Westernized

and losing its Chinese identity. The government responded with a Speak

Mandarin campaign that featured local celebrities on billboards urging people

to not lose their mother tongue to English. So in 2008 these Speak Mandarin ads were all

around Singapore at the same time as everyone was complaining about too much

Mandarin being spoken. It seemed to me that Chinese Singaporeans cherished their

heritage until real Chinese started showing up and not acting British enough.

Hence, a Speak Good English movement competed for billboard space at the same

time as the Speak Mandarin campaign.

The peculiar icing on the cake, however, was that the

complaint a few years earlier was the opposite: that Singapore was becoming too Westernized

and losing its Chinese identity. The government responded with a Speak

Mandarin campaign that featured local celebrities on billboards urging people

to not lose their mother tongue to English. So in 2008 these Speak Mandarin ads were all

around Singapore at the same time as everyone was complaining about too much

Mandarin being spoken. It seemed to me that Chinese Singaporeans cherished their

heritage until real Chinese started showing up and not acting British enough.

Hence, a Speak Good English movement competed for billboard space at the same

time as the Speak Mandarin campaign.

Other divides became easily apparent. At one job interview,

an employer mentioned out of the blue that she could never trust an Indian’s

resume: “They all lie.” Likewise, my first landlord told me I was welcome to

bring home friends, “Just no Indians.” When I searched for new accommodation, I

was frustrated by how many ads stated, “No cooking.” There was one room I

really liked, but I wasn’t fond of the cooking ban. I asked the landlord if he

was really strict on that; after all, there was a kitchen in the flat. “We just

say ‘no cooking’ to keep the Indians away,” he explained. “They love to cook,

so they won’t look at a place with a no-cooking rule. But you can cook, that’s

okay. Just no curry.” (I didn’t rent that place.)

Other divides became easily apparent. At one job interview,

an employer mentioned out of the blue that she could never trust an Indian’s

resume: “They all lie.” Likewise, my first landlord told me I was welcome to

bring home friends, “Just no Indians.” When I searched for new accommodation, I

was frustrated by how many ads stated, “No cooking.” There was one room I

really liked, but I wasn’t fond of the cooking ban. I asked the landlord if he

was really strict on that; after all, there was a kitchen in the flat. “We just

say ‘no cooking’ to keep the Indians away,” he explained. “They love to cook,

so they won’t look at a place with a no-cooking rule. But you can cook, that’s

okay. Just no curry.” (I didn’t rent that place.)

Any other races or nationalities looked down upon? Well,

yes. Malaysians. A thread commonly whispered was that Malaysians were less

employable in professional positions because they were lazy or not as well

educated. And don’t get me started on what I heard about Filipinos.

This isn’t to say that racism was rampant in Singapore.

Practically none of my close friends thought along those lines. But the fact

that these sentiments were so easily come across was evidence enough that there

were racial troubles brewing under the surface of neat-and-tidy Singapore.

Which is why the bus strike, the first labour walk-out in

Singapore since the mid-1980s, did not surprise me. Here’s why – it was over a hundred drivers from China who refused to go to work that morning in

November. Many of them have since been deported, and a few of them jailed. The trade union that supposedly protects its workers has an entrenched

policy of paying China citizens less than Malaysians, who are paid less than

Singaporeans. The China workers were fed up with the pay discrepancy, as well

as their dormitory living conditions. The media and the blogosphere were set

alight.

Finding a voice sympathetic toward the drivers was rare.

Most of the comments I came across online and reported in the media were mostly

hostile toward the drivers; sentiments along the lines of "go home". That, too, didn’t surprise me. When the MRT

(subway) had a major rush-hour breakdown earlier this year, the press reported

members of the public blaming the influx of foreigners placing too much stress

on the system (a complaint that conveniently ignores the fact that foreigners

occupy jobs that would otherwise be held by somebody else, so the trains would

still be carrying the same number of passengers going to and from work regardless of where they came

from). Then there was the car accident where a Chinese citizen ran a red light

(admittedly at horrific speed) and killed three people. Rather than being

reported as an isolated tragedy, the public wilfully ignored the hundreds of

Singaporeans killed by other Singaporeans on the roads every year, and latched

onto this one incident as an excuse to heap scorn on foreigners. The

parliamentary elections that followed shortly afterward saw the ruling party’s

vote-share drop to a historic low based on sentiments that the government was

allowing in too many foreigners, who were killing citizens on the roads,

destroying the MRT, and generally ruining Singapore’s clean and efficient way

of life. And now look at them, going on strike and paralysing the bus system!

But here is the unfortunate reason why Singapore has settled into this race-based class system: without the cheap labour provided by foreign workers, the cost of living would be unacceptable. Bus drivers paid liveable, equal wages would result in higher fares. Getting good, English-speaking service in retail and F&B establishments would require hiring Singaporeans, who would command better pay, raising the price of eating out. The same for getting Singaporeans to work in construction or other kinds of manual labour. Imagine the cost of HDB flats built not by Bangladeshis, but by Singaporean workers who demanded professional construction salaries. I know that Singaporeans think their city is already too expensive, but I don’t think they truly appreciate how the high level of cheap foreign labour keeps their cost of living from going up to London or Manhattan levels.

Any Singaporean who has read this far will want to debate my

presentation of the facts. And there is a lot of room for debate and alternative viewpoints within what I’ve written. What I’m sure everyone will agree on, however, is

that the problems I talk about do exist.

What are the solutions? As someone who loves Singapore and feels it is "home" in many ways (yes, I'm thinking of returning), I view its race and class relations through the lens of my experiences growing up in a city that had its own landscape changed by immigration, where today half our population is made up of visible minorities. I was born in the 1960s. Vancouver was a very white city during my youth, and I witnessed the city's reaction to the influx of Asians through the 1980s and 1990s. There were the typical blue-blood cries and moans about immigrants and their lack of respect for our values, the death of English, crime committed by "Asian gangs" and so on. The right-wing editorials in the press back then would be horrifying and unpublishable by today's standards.

But we got over it. And I'll illustrate why.

In Vancouver, among my friends are three bus drivers, two

grocery-store clerks, a bank teller, a landscaper, two Starbucks baristas, a

gas-station attendant, two warehouse shipper-receivers, and a few retail

clerks. And then I also have friends who have professions that might be considered status jobs: architects, urban planners, police

officers, doctors, government workers, graphic designers, and the like. Whether we are blue-collar or white-collar, we socialize together, equals among

friends.

And here’s another thing: none of these professions, from the bus

driver to the architect, are exclusive to or dominated by any particular race or

nationality. We have locals who pick up the garbage, and immigrants who become their bosses – and vice versa. It's difficult to pick on foreigners for "taking our jobs" when we all serve each other, or to blame them for "changing our way of life" when the changes immigrants make become our way of life.

Many of my friends came to Canada as immigrants. Not one ever had to live in a foreign-worker dormitory. Not one was explicitly paid less for his work because he came from a certain country. That, too, makes a huge difference in a sense of equality and belonging to a place.

In justifying the lower pay for China workers, the bus

union’s representative said that foreigners are less likely to settle in

Singapore and make long-term contributions to society. But this is a Catch-22.

What incentive does a bus driver from China have to settle in Singapore when he is paid and treated as a disposable member of the country he lives in? When he is given a wage

($1,075 a month) that does not allow him to get out of the foreign-worker

dormitory?

|

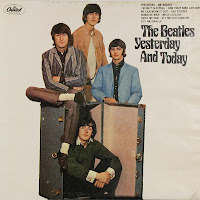

An ad in Singapore for white

chrysanthemum tea |

It must seem odd that I, as a white Westerner, would be so

engaged in these issues. In Singapore, I was considered to be among the

privileged class – the “ang mo”, as Singaporeans called us whiteys. We were far

removed from the problems of the foreign workers, and in fact benefited as much

or more from their services. But the fact that white people are so privileged

in Singapore is one of the problems contributing to Singapore’s race/class

dysfunction. Even without a university degree, I could command a higher salary

than a Malaysian with a BA. In a truly healthy society, no race, no nationality

should be considered better, worse, more powerful, less important, or less

valuable than any other.

One of the complaints in Singapore that I haven’t touched on

is about the behaviour of the China nationals who migrate to that city. It’s

not just the language issue (“I can’t get service in English”) but the fact

that the rapid influx has brought “mainland manners” (shoving in queues, spitting,

and a general abrasiveness) to a society that has been born and bred with an

antiquated politeness inherited from austere British colonists. This culture

clash is at the heart of Singaporeans' complaints about the mass migration.

Understandable, I suppose.

But then I have to wonder: Vancouver has experienced the

same influx of mainland Chinese and we don’t have nearly the same problems

here. About 40 percent of our population is Asian (and another 10 percent other

visible minorities). One of our suburbs, Richmond, is famously 60 percent

Chinese. Some racial tensions do surface from time to time, but nothing to the

extent where a single traffic accident causes a xenophobic outburst on the

front pages. (The Singapore media dubbed it “the Ferrari crash”, I assume to

underscore the wealthy driver’s sense of privilege. If he had been driving a

Corolla, how much do you think the press would have enjoyed calling it “the

Toyota crash”?)

Another reason there are more culture clashes in Singapore,

I believe, is because the foreign workers, being paid less than Singaporeans

and housed away from the locals, are not instilled with any sense of belonging

or responsibility toward the country they live in. Even for those who are wealthy and in professional positions, such as the Westerners (and even

some from China, as the Ferrari driver was), Singapore makes it more conducive for them to stick together among their own

national enclaves and not mix with the society in which they serve. As a result they don’t adapt their attitudes or

expectations. The Singapore government is quite complicit in fostering these attitudes as well. Not only have they pitted foreign workers against the locals by providing them with lesser wages and living conditions, they have also pitted their own people against wealthy migrants by classifying them as "foreign talent" and essential to sustaining the nation. Locals rightly feel annoyed and offended by that arrangement; their own government doesn't believe they alone are talented enough to sustain the country?

Another reason there are more culture clashes in Singapore,

I believe, is because the foreign workers, being paid less than Singaporeans

and housed away from the locals, are not instilled with any sense of belonging

or responsibility toward the country they live in. Even for those who are wealthy and in professional positions, such as the Westerners (and even

some from China, as the Ferrari driver was), Singapore makes it more conducive for them to stick together among their own

national enclaves and not mix with the society in which they serve. As a result they don’t adapt their attitudes or

expectations. The Singapore government is quite complicit in fostering these attitudes as well. Not only have they pitted foreign workers against the locals by providing them with lesser wages and living conditions, they have also pitted their own people against wealthy migrants by classifying them as "foreign talent" and essential to sustaining the nation. Locals rightly feel annoyed and offended by that arrangement; their own government doesn't believe they alone are talented enough to sustain the country?

The reason, I believe, that Vancouver doesn’t have the same

magnitude of ethnic clashes is because the cultures here mix and must work

together to get the benefits of the society – both socially and in the workplace. An

immigrant from mainland China, for instance, not only has to get along with

Caucasians, but others from Taiwan, Malaysia, India, Korea, Iran, etcetera.

They all tone down any national characteristics that might

cause friction amongst each other, because they're here for the long term. They also have the carrot of citizenship

dangled in front of them, so there’s more feeling of belonging and civic

responsibility. They are treated by our governments as potential Canadians (whether a janitor, construction worker, nurse or executive), not divisively pigeonholed as transitory "labour" or high-class "talent".

Singapore has prospered well under the tacit segregation of

foreign labour, but I have a feeling that the cookie is starting to crumble. I

can only foresee more issues of discord and unrest relating to race-based

inequality. Singaporeans talk about limiting foreign migration as a solution, but I think the solution needs to look at a larger picture. The society has to become more

egalitarian. It would take completely different policies from the government to

attract foreigners for very different reasons than they do now. At present, Singapore makes it very attractive for foreigners, rich and poor, to stay for a few years, make some cash, and leave. They have not created a fabric of society that actively encourages people to immigrate and take citizenship. To do that, Singaporeans would have to shift their own thinking and accept a higher cost of living, and young Singaporeans would have to enter occupations they normally wouldn’t engage in. It would require a massive shift in thinking that could take generations.

If the government and the people aren't willing to do that – to essentially enter an era of first-world thinking with regards to immigration, equal pay and human rights – then they should expect the same social clashes to surface time and time again.

-----------

Further reading:

The problem of a racialised mind, Today newspaper, Singapore: Oct 11, 2012

Foreigner issues garner most feedback this year, Today newspaper, Singapore: Dec 14, 2012

Ferrari Crash Foments Antiforeigner Feelings in Singapore, Wall Street Journal, May 25, 2012

When the invitation for the Caran d'Ache product launch at

the Shanghai Concert Hall landed on our desk, we were intrigued. If we hadn't

known that Caran was the Swiss producer of absurdly expensive pens for those

who wouldn't be caught dead with a Bic, we might have assumed they were

watchsmiths. It was that vague.

When the invitation for the Caran d'Ache product launch at

the Shanghai Concert Hall landed on our desk, we were intrigued. If we hadn't

known that Caran was the Swiss producer of absurdly expensive pens for those

who wouldn't be caught dead with a Bic, we might have assumed they were

watchsmiths. It was that vague.

.jpg)